Futuristic Readings No.4 -2020

Iraqi New Government & the Economic Crisis in Kurdistan Region “Constraints and Scenarios”

– Futuristic Readings No.4

– Researchers: Dr. Yousif Goran, Dr. Omed Rafiq Fatah, Dr. Abid Khalid Rasul, Dr. Hardi Mahdi Mika

– Centre for Future Studies – Sulaimani – Iraqi Kurdistan Region

– April 2020

Contents

Section One: The Future of the Al-Kadhimi Government; Duty and Constraints

Section Two: The Economic Crisis in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq; Deep Roots and a New Reemergence

Introduction:

In Iraq and the Kurdistan Region issue of good governance, its constraints and challenges, and the prospects for reform are constantly on the political agenda. Where new crises or events emerge the need for an answer to these issues is further underlined. This is in particular the case today as both jurisdictions are juggling several competing crises; the continued difficulty in forming the new Iraqi government, the nationwide economic crisis stemming from the collapse of the international oil price, and the inability of both governments to fulfil their financial obligations as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (which at present is in its early stages in both Iraq and the Kurdistan Region) and its implications. These crises have each become significant obstacles to the future governance of both jurisdictions, so much so, that attempts to confront them have consumed their and long and short-term political agendas.

The fourth issue of Ranan discusses these obstacles and challenges, examines Iraq and the Kurdistan Region’s ability to confront them and, in two sections, puts forward the possible scenarios going forward.

Section One:

The Future of the Al-Kadhimi Government; Duty and Constraints:

Following several months of unrest and political deadlock in Iraq, on 7 May 2020 the Iraqi parliament voted in favor of the cabinet of Iraqi “third successive prime minister designate”, Mustafa Al-Kadhimi, and its political program. After the resignation of Adil Abdulmahdi on 30 November 2019, under pressure from southern Iraqi protestors who were demanding an end to corruption and government of the elite, Iraq was governed for almost five months by a caretaker government.

Al-Kadhimi’s proposed cabinet and its political program was given the nod with similar ease as Al-Kadhimi’s selection as prime minister designate. In contrast to the prime minister designates that preceded him, Mohammed Allawi and Adnan al-Zurfi, Al Kadhimi’s selection as Prime Minister designate and his acceptance by the Iraqi parliament was a somewhat untroubled affair. For Mohammed Allawi, his bid to form the new Iraqi government failed in the final throws when the Iraqi parliament refused to convene, while for Adnan al-Zurfi his attempt to form the new government failed when his candidacy was withdrawn after three weeks after his selection. Al-Kadhimi was able to secure internal support from across the Iraqi communities (Kurds, Sunni and Shia) and receive tacit nods from both the United states and Iran. Furthermore, Al-Kadhimi was able to side step protestors, who found themselves subject to a national lockdown as a result of the spread of COVID-19 in Iraq. Al Kadhimi was also able to select his cabinet with little disagreement from Iraq’s power brokers and received overwhelming support from the Iraqi parliament. Therefore the current question regarding the new Iraqi government are: Can the new cabinet rescue Iraq from its multiple crises? What is the duty of the Al-Kadhimi government? What must it do? What can it do? And what will its future be?

– The Duty of the New Iraqi Government:

Given Al Kadhimi’s and his cabinet’s political program, his pledges to the Iraqis when after his selections as Prime Minister designate, the conditions on him and his government by Iraqi power brokers, the pressure from the Iraqi streets and the influence of foreign powers in Iraqi internal affairs, the al-Kadhimi government has several obligations. The key obligations for the government are;

- Solving the Iraqi economic crisis through a new emergency budget specific to confronting the collapse of the international oil price through the development of other economic sectors;

- Containing the COVID-19 pandemic in Iraq;

- Tackling corruption;

- Disarming Iraqi militias and returning arms in Iraq to state control;

- Holding early elections while insuring the implementation of the Iraqi law that governs political parties in Iraq;

- Developing the concept of Iraqi citizenship, institutionalizing the discussions with the Iraqi protest movement and responding constructively to their demands;

- Insuring the return of Iraq’s internally displaced peoples to their original home provinces and rebuilding the towns and cities that were destroyed as a result of the war against the Islamic State;

- Strengthening Iraqi sovereignty through by reducing foreign interference in Iraqi internal and external politics;

- Confronting terrorism and providing internal security for Iraqis;

- Calming relations between Baghdad and Erbil and working to resolve the outstanding issues between them;

- And other minor obligations.

The list of obligations for the Al-Kadhimi is extensive. Its priorities will likely be prioritiesed by the extent to which the relevant Iraqi lobbies are able to influence the government. However, Iraq’s current state demands urgent action on the economy, COVID-19 and preparing the groundwork for early elections.

– What can the Al-Kadhimi government do? Constraints and Scenarios:

The many competing aims and obligations of the Al-Kadhimi government means promises its work to be difficult and challenging. Iraq’s economic crisis, which shows no sign of abating, is arguably the governments primary challenge. The second most pressing challenge is the ever-present threat of a second wave of protests by the Iraqi protest movement if Al-Kadhimi fails to respond their demands. Third, the actions of Al Kadhimi’s government will likely be restrained due to the political tight-rope it must walk. The government must constantly insure it does not lose the confidence of the Iraqi power brokers whose support insured the cabinet also received parliamentary support that led to Al-Kadhimi becoming the Iraqi Prime Minster. If these power brokers lose confidence in Al-Kadhimi and his government then he and his cabinet may follow a similar fate to his predecessor the former Iraqi prime minister Adil Abdulmahdi and his cabinet. Al-Kadhimi’s strength is in his image as an unbiased, independent and militia-less prime minister. If he was to lose this image amongst Iraqi power brokers then it could lead to his removal from office. Fourth, Al-Kadhimi’s government faces continued challenge from the battle for influence in Iraq between the United States and Iran. Fifth, the Iraqi government faces a continued challenge from the ambient threat of a resurgence of terrorism in the country.

Therefore, the challenges facing the Al-Kadhimi government and it aims and objectives, are numerous. However, two challenges are arguably most prominent;

- Internally: Al Kadhimi’s government is challenged by the competing objectives and expectations of the Iraqi protest movement and the traditional political power’s in Iraq who make up the Iraqi government. The former is demanding swift action from the Iraqi government to implement reforms to restrict the corruption of Iraq’s traditional powers, while the latter is hoping that the change of government and the changing of faces at the ministerial level will calm tensions in Iraq and allow them to continue to benefit from the Iraqi arrangement.

- Internationally: Al Kadhimi’s government is challenged by the competing objectives and expectations of the United States and Iran for the Iraqi government. The will of the United States is to strengthen Iraq’s independence and to see reforms in Iraq’s security agencies to reduce the influence of Iran and Iranian backed militias. On the other hand, Iran wants to see the Iraqi government commit to remaining supportive of its attempts to counter United States power in the region and to allow Iraq to remain an avenue for Iran to evade international sanctions.

– Future Scenarios for the new Iraqi Government:

Scenario 1: While achieving all or most of its aims and obligations is unlikely, we can argue that Al-Kadhimi’s government will likely achieve some of them if it can overcome its central challenges. For example, it may record some successes economically or it may continue to receive support from Iraq’s power brokers until the government achieves its primary purpose of calming tensions in Iraq by working to prevent a second wave of protests in the country, which will work in favor of Iraq’s ruling elites and powers. This arrangement may continue until 2022 when Iraq is due its next parliamentary elections (if an early election is not called before then).

Scenario 2: If the challenges that have already been outlined continue to mount for the Al-Kadhimi’s government; for example, if the Iraqi protest movement begins a second wave of protests, if the power brokers in Iraq decide to withdraw their support for Al-Kadhimi or if Iraq’s economic crisis continues to worsen to the extent that it is unable to pay salaries to state employees, then the Al-Kadhimi government will likely end up resembling a caretaker or interim government whose only task is to prepare Iraq for early elections. However, even the task of a government of this kind will not be without obstacles. The United States may find such a resolution unacceptable as it does not want to see early elections in Iraq. The United States currently has influence over Iraq’s three leadership positions (president, prime minister and head of parliament), an arrangement it does not want to soon lose.

Scenario 3: If the crises in Iraq continue to deepen and Al-Kadhimi’s government is deemed to have failed to meet its obligations, then it may face the same outcome as the previous government of Adil Abdulmahdi. In this scenario, Iraq will once again be plunged into political disarray stemming from the county’s pre-existing national and international political rivalries, long-term constitutional disagreements will resurface, the influence of militia forces will increase, protestors will mount further pressure on government, and Iraq will likely see a rise in populism. Furthermore, the country will succumb to further unforeseen consequences that neither, Iraq, its people, nor its traditional political forces can withstand.

Section Two:

The Economic Crisis in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq; Deep Roots and a New Reemergence:

– The Reemergence of Crisis:

The economic crisis in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq started much earlier than that of Iraq, However, it was its response to the COVID-19 pandemic that shed new light on the meager state of the Kurdistan Regional Government and its finances that it had managed to keep veiled for several years. This is not to say that the pandemic only impacted the economy of the Kurdistan Region as it also impacted the coffers of many governments and large companies around the world. One such government was that of Federal Iraq, a government that pays the salaries of 25 percent of the residents of the Kurdistan Region directly as a result of prearranged agreements between the two jurisdictions. A cocktail of crises in Iraq, including the reemergence of COVID-19, the continued fall of the international oil price, the protests in Iraq and the change of government in Baghdad led to the Iraqi federal government taking the decision to halt the payment of state salaries to these residents laying bare the problems of governance in the Kurdistan Region and its financial shortcomings. The non-payment of salaries by the Iraqi government broadened the economic problems for the KRG, impacted the finances of the residents of the region and damaged the relationship between the region’s political parties. As a result spontaneous protests erupted across the Kurdistan Region, the most potent of which was the protest by state sector employees in Duhok, which had both political and security consequences. To understand the level of this crisis for the KRG and identify the source(s) of its shortcomings we must examine the management of KRIs sources of revenue and the distribution of this revenue across the different sectors of the Kurdistan Region’s economy.

– An Examination of the Statistics Detailing the Kurdistan Region of Iraq’s Income and Expenditure:

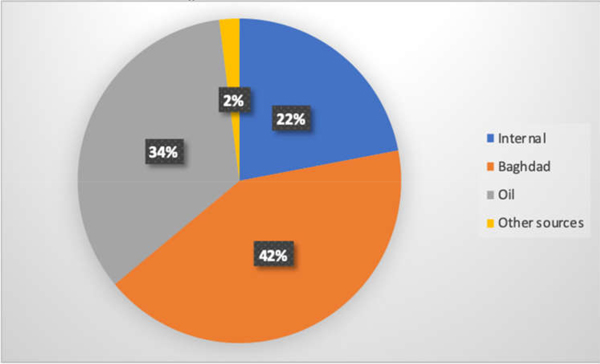

According to the available data, in the period before the reemergence of COVID-19 the KRG’s Ministry of Finance had monthly income as follows:

Internal income: IQD 40 billion; Oil income: IQD 360 billion; Income from the Iraqi government: IQD 452 billion; Other sources: Approximately IQD 20 billion, (see Figure 1) for the percentage figures. From this income the KRG spends IQD 886 billion on public sector salaries, IQD 200 billion on ministerial spending and IQD 35 billion on infrastructural projects.

However, in March and April, following the outbreak of COVID-19, the subsequent collapse in the international oil price and the implementation of a national “lockdown” in the Kurdistan Region the KRG’s income plummeted. It lost 45 percent of its oil revenue and 90 percent of its internal income. If the COVID–19 crisis and the falling oil price continued then the financial shortcoming of the KRG would likely have been IQD 200 billion. Furthermore, as already outlined during this period the Iraqi government had also halted its payments to the KRG, which previously made up 42 percent of the KRG’s total income.

Therefore, the crisis revealed some uncomfortable truths about the KRG’s sources of income, its spending and the unstable nature of these income streams.

Figure 1: KRG’s sources of income

Source: Centre for Future Studies

– Understanding the Roots of the Crisis and the Nature of the KRG’s Problematic Income Streams:

The current economic state of the KRG is not solely a result of the fall-out from the COVID-19 pandemic, the poor state of international markets or relations between Baghdad and Erbil. Instead, the problems are endemic in the economic model and structure of the Kurdistan Region. Its income streams, expenditure and lack of long-term planning are all contributing factors as they are by their nature problematic. Continuing without economic reform will likely result in a further deepening of the economic crisis and disaster in the near future.

The question here is why is the economic crisis deeper in the Kurdistan Region then in Iraq and why is the source of the crisis internal more than it is external? To answer this, we must examine the Kurdistan Region’s sources of income;

- The implementation of a consumerist economic policy: this economic policy is troublesome and has become a significant obstacle to the diversification of the KRG’s sources of and the KRG’s spending habits. In large part, the problem relates to the imbalance between the stability of the KRG’s spending and the instability of its income streams. The production of a consumer economy relies on three conditions being met:

- Having in place an economic contract based on an agreement between political as well as smaller groups, which has political implications;

- The continuation of a contract for a period of time synonymous with the lifespan of the parties covered by the contract. In other words, the smaller groups covered by the contract live of the proceeds of economic growth without having to contribute to the state and are only called upon to support the political groups during times of political upheaval or elections;

- The existence of an arbiter or political dealer.

This economic policy is a problem because it has a negative impact on two key areas: First, it paves the way for political and economic corruption that burdens the state financially. In the Kurdistan Region a consumerist economic policy has resulted in secondary problems, the region lacks measures to reinvest its capital in real infrastructural projects as the arbiters or dealers live on the proceeds of ‘made up’ projects, which are given the go ahead and funded by the KRG. Furthermore, as the worlds of politics and business have intertwined in the Kurdistan Region, business projects have become monopolized by the elite and funded by the KRG. While some may argue that this promotes investment, this is not the case as those monopolizing the market are not investors. One would expect an actual investor to have a transparent income independent of the state.

In the Kurdistan Region, permission for investment and business projects are strongly attached to geographic factors, namely in which towns or cities projects are permitted to go ahead. As business is intertwined with politics, the decision of location is often tied to political benefit rather than economic necessity. Therefore, in the Kurdistan Region, one often finds investment and business project concentrated around those areas where politicians wish to win votes, in essence allowing politicians to use these projects to buy votes. This practice leads to an imbalance in project distribution across the region and investors not being able to meet their original objectives as the projects take on new political aims and do not develop the regions economy

- The source of income is dependent on oil: 34 percent of the Kurdistan Region’s income is dependent on its oil sales and 42 percent of its income is dependent on the Iraqi Federal Government, which itself is 90 percent dependent on sales of Iraqi oil. Therefore, 76 percent of the Kurdistan Region’s income is directly or indirectly dependent on the sale of oil and its price internationally.

- A portion of the Kurdistan Region’s income is dependent on short-term and unstable political relations: another problem associated with the Kurdistan Region’s sources of income is that the majority is dependent on political relations between the government’s in Erbil and Iraq and not long-term bilateral agreements that depend on national strategic planning. For example, the 42 percent of income that the Kurdistan Region previously received from the Iraqi Federal Government is awarded based on its inclusion in Iraq’s annual budget. This inclusion and percentage is subject to change and, therefore, requires continued negotiations and compromise and is dependent on the Kurdistan Regions relation’s with the governing coalition at the time in Iraq (where it should be dependent on state relations between the Kurdistan Region and Iraq). More worrisome for the Kurdistan Region is that the inclusion of the Kurdistan Region’s share of the Iraqi budget also requires annual parliamentary approval. This parliamentary ratification is in itself problematic on several levels. While the parliamentary decision has the potential to impact the Kurdistan region’s economy negatively, it also worked to set back Kurdistan Region’s long-term national aspirations, stall progress on a resolution to the status of the Iraqi disputed territories, weaken questions around Kurdish identity and territory, and weaken the Kurdish agenda in Baghdad.

Furthermore, the sale of Kurdish oil in international markets is also dependent on short-term and unstable relations between the Kurdistan Region, their neighboring states (Turkey and Iran) and international oil companies and businessmen. They are not organized around a single Iraqi oil and gas law that will guarantee compensation for the sale of Kurdish oil by the Iraqi government. The current structure of the Kurdish oil market means it is perpetually at risk of being halted. Furthermore, international competition to attract buyers forces the KRG to sell its oil at significantly discounted prices.

Another portion of Kurdish finances is dependent on the state of terrorism in northern Iraq and financial support from is international partners to counter the threat. For this, the KRG is reliant on good relations with its international partners in the international coalition against the Islamic State, which is once again a short-term arrangement.

- According to reports from the Kurdistan Region’s parliamentary committees and the statements and publications from the KRG’s Ministry of Finance and the Kurdistan Regional Government, the Kurdish government has yet to gain control complete over its sources of income. Corruption and wasteful spending allow for government finances to go in to the pockets of an elite few who have sway within the region’s dominant political parties, as well as several other forces outside of the Kurdish political sphere. Finances are funneled through numerous avenues including check points, customs, companies that have been forcefully linked to the government, customs amnesties for some companies, non-payment of debts by companies who have taken out government issued debts, corruption and border crime. The KRG admitted that some of these activities were contributing to the weak state of the Kurdistan Region’s economy in a government meeting held on 5 May 2020.

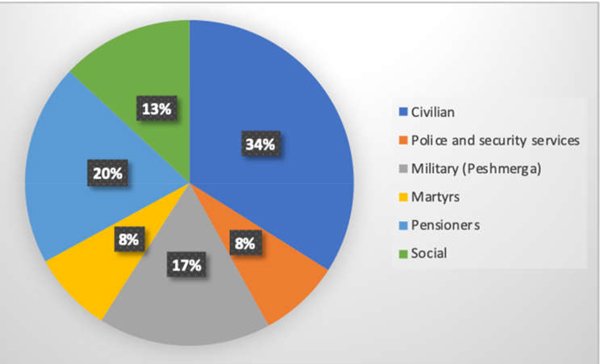

- Another problematic character is the KRG’s spending and revenue sharing in the region, especially regarding the way it distributes its income between the different economic sectors. According to the latest data from the KRG’s biometric registration scheme for its residents the KRG has 1,200,273 individuals on its payroll. These individuals are distributed as follows;

- There are a total of 752,959 state government employees, which make up approximately 60 percent of all the individuals on the state payroll. They are as follows: Civilians: 430,231 individuals; Police and security forces: 104,699 individuals; Military: 217,979 individuals.

- The remaining 40 percent (447,364 individuals) are on the state payroll as follows: Martyrs: 97,937 individuals; Pensioners: 246,269 individuals; Social: 159,157 individuals.

- If we view the division of these employees across the different sectors they read as follows: Education: 2 percent; Health: 6.5 percent; Interior: 19.1 percent; Military (Peshmerga): 18.7 percent (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The division (by %) of individuals on the KRG’s payroll.

Source: Centre for Future Studies

These figures reveal a significant imbalance in the KRGs military and security spending compared to its spending on health and education. Almost 37.8 percent of those on the state payroll (state pay taking up the majority of the KRG’s expenditure) are serving on the KRG’s military and security services. In contrast, employees in the health and education sectors, arguably two of the most important state sectors, only makeup 28.7 percent of state employees. Furthermore, those on the state payroll without being employed in any sector, “ghost employees”, those that have two salaries for the KRG and high-level pensioners have also become a wasteful financial burden on the KRG’s coffers. These payments are unproductive and rarely have a return for the KRG.

More concerning than the above figures was the statement by the Prime Minister of the Kurdistan Region on the eve of Eid 2020, where he revealed the state of the KRG’s finances explaining that “70 percent of the Kurdistan Region’s income is spent on 20 percent of the population”. This statement is a reflection of the figures outlined above which have worked over many administrations to restrict the ability of the KRG to reorganize its finances.

Here it becomes clear that the implementation of a consumerist economic policy that relies on an oil economy (which according to economists provides for one of the most unstable economic models and that are at times of crisis the most wasteful), unstable political relations and the poor distribution and organization of wealth has worked to create disaster and crisis for the economy of the KRG.

– Future scenarios and a proposal for reform:

By taking into account the current state of the Kurdistan Region’s economy two possible scenarios can be put forward:

First scenario: It is clear that the Kurdistan Region of Iraq’s economy is at risk, so much so, that it has weakened itspolitical standing nationally and internationally. Therefore, in the near future it is unlikely that the economy of the Kurdistan Region will return to the highs it enjoyed before 2013. Instead, in the short-term the Kurdish economy may retract further. If national and international events continue on their current trajectory and no reforms are implemented then this economic retraction may also become long-term.

Second scenario: The first scenario can be avoided if a united political will emerges amongst Kurdish decision makers to push the KRG towards implementing fundamental reforms. These reforms should be targeted to offset many of the potential negative consequences of inaction that include economic collapse and political fragmentation. In order for this scenario to become a reality, a new plan is required to rescue the region from this economic crisis. The points outlined below can assist in forming such a plan:

- The “Reform Law” should be implemented in a comprehensive and just manner, and its scope widened to other public service, the judiciary, and the legislature.

- It is important that in reordering the public sector, thorough thought is given to the balanced and just redistribution of public funds. In this reordering the focus of the KRG must be on job creation rather than providing unsustainable government employment. To achieve this, the KRG must increase its investment budget, promote small enterprise and implement a robust social security system for non-government employees.

- The Kurdistan Region should diversify its economy away from oil by promoting and supporting other industries, such as food, consumer products, petrochemicals, tourism and agriculture among others. Success in each sector requires the neccessary rules and regulations.

- The Kurdistan Region should work to shrink the size of the state and make it more active. This can be achieved through the merging of ministries and departments, as well as, implementing administrative and fiscal decentralization to improve government efficiency and developing local administration.

- The Kurdistan Region should work to reduce the non-civilian budget (currently at 37 percent), which at present does not correspond to international standards and is unsustainable for the KRG. Savings should be redirected to the investment budget, job creation, supporting small enterprise and infrastructural project.

- The Kurdistan Region should establish a trusted and independent banking system to promote further economic growth, a financial cycle and the use of saved and hidden capital.

- The Kurdistan Region should work to implement new rules and regulations to strengthen and liberate the private sector and its agencies, oppose market monopolization and distance politicians and officials from the business world.

- Implementing an active and just system of taxation that covers all those that hold capital in the region.

- To return stability and reduce economic and financial nervousness, it is important that the Kurdistan Region works to resolve the outstanding economic issues between Erbil and Baghdad through the provisions of the Iraqi constitution. Restoring trust between Erbil and Baghdad can play a significant role in developing and broadening business and economic prospects for both sides, which will subsequently create bigger markets for both.

- The Kurdistan Region should re-establish the foundations of the education, social affairs and higher education ministries in a manner that promotes pragmatic education tied to local market needs. This will go a long way in developing a young skilled population that is ready to enter into employment in the Kurdistan Region’s different sectors different sectors of the Kurdistan Region.

English

English كوردی

كوردی العربية

العربية